Above, you're looking at the gorgeous art of Kevin Nowlan. At the left, the way the art looked in the 1980's. At the right, the original art for sale at the Heritage Auction website.

You can see considerable fading in the original. Toward the lower right, some of the color has almost completely disappeared.

This comes from using dyes instead of pigmented paints.

You know those Copic markers I keep warning you about?

Those are dyes. This Dr Strange piece was painted using the old Dr Martin's Concentrated Watercolors. They were not watercolors, they were dyes. Almost all cartoonists used them, and almost all cartoon art painted just a few decades ago has paid the price. Colorist Jose Villarubia who posted this comparison on his Facebook account, is one of many creators who regularly post warnings about using dye based art/design tools.

Two years ago, I posted about the dangers of Copics on my twitter and got excoriated by fan artists, some of whom called me a liar and claimed I was only complaining about Copics to get attention and Youtube views.

Seriously?

Whatever you say, kiddo, it's your art's funeral.

Also, they claim that artists who are concerned about the longevity of their art are "pretentious".

Sure, when some museum picks up a piece, or some collector drops a wad of dough on a piece of art, what do I care if it fades to the brilliance of a piece of toilet paper once it's out of my hands?

Were these people raised by wolves?

You're looking at two scans of a Barry Windsor Smith Conan piece. On the left, the original printing from Smith's1970's era imprint The Gorblimey Press. On the right, a recent scan of the art from Heritage Auctions.

What the bloody hell happened here?

The print on the left may or may not reflect Smith's original intention. But it looks to me like a typical Smith palette. However, there is no way to tell without a time machine.

The color shift on the right was so extreme, there is speculation it was a repaint. It's not. The brush strokes match.

Smith was known to paint with a combination of watercolor as well as the old Dr Martin's - the watercolor that's actually a dye.

What we see on the right may be a chemical reaction to the combination of the watercolor and the dye.

Also, dyes often contain fluorescents - they fade faster than anything else. This is especially true with colors in the magenta range. On the left you see a lot of purple and pink in the palette. On the right, this is almost completely gone.

Two things are likely here. On the left, the art would have been shot and printed using the old photo web press process. On the right, you're looking at a digital scan.

The old photo/web process was more accurate in capturing the colors of the dyes. In a computer scan, the fluorescents turn toward a harsh magenta. What your eye sees is not what the scanner sees. It is almost impossible for a computer scan to get a true scan of work made with dyes.

Also, even if this art is kept away from possible light damage, dyes break down regardless. The "paints" contain no binder. Over time, their chemicals break down. Note how much pink and red there was in the sky on the left. But on the right, there is almost nothing but blue and yellow left. All subtlety and light is gone.

We'll never know Smith's original intent, because the intent no longer exists, and this color shift occurred in just a few decades. Since Smith self published the original print on the left, I have to assume this is a closer reflection of what he wanted to achieve. And that the print has not faded measurably in the years since.

One of the interesting things about this piece is how it was created. Almost no one works this way anymore, but it produces great results. Look at the below image.

This is the actual painting. This technique is called blue line color, which I’ve written about before. What you are seeing here is a copy of the line art printed in non-photo blue on a piece of fine art paper. The printer's camera cannot see that particular shade of blue. (More properly, as Mark Wheatley pointed out below, the camera is set up to NOT see that particular shade of blue for the purposes of this printing technique. It can see the blue if you want it to. Read comments for more info.)

The black line art is printed on a sheet of clear acetate. You can see production notes written on it.

This is the colored page with production notes.

And the final art combined.

The little + marks are register marks that the printer uses to line these two images up perfectly for final combination and print.

Now, why would anyone work this way?

Well, this is all pre-computer. If you wanted to print painterly comic art back in the day, but you also wanted to print it with very clean line art that didn't get muddied up when you went over the lines with color, this is how you worked. I worked this way a few times myself.

I remember being in the Marvel offices about twenty years ago, and an editor was enthusing about this artist who had come up with this cool new technique to paint comics! He actually did the painting on line art without a computer!

And I had to explain to the editor that this new technique was old school, and that artists had been using it for decades.

Only ten years after computer coloring had taken over the industry, people had forgotten about blue line color.

Let us pause a moment to shed a tear.

So why doesn't everyone work this way now?

Well, it's harder than digital color, for one.

Also, when you paint on the paper, the paper tends to warp a bit. So it's tricky to line up the lines on the top layer when the art on the bottom layer changes shape slightly. Where blue line peeps through, it prints white.

Also, over time plastic changes shape. This can be due to heat or humidity. So if you look closely at the scans, you see a bit of warping and flex in the line art which is not apparent in the original Gorblimey Press print. In the long term, this art doesn't hold up very well, especially if you painted it with dyes.

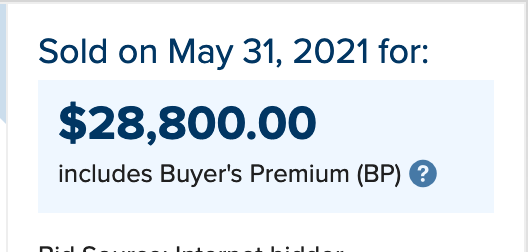

This did not stop this piece, which was from artist Jim Steranko's collection, from selling for a tidy sum.

I wouldn't call this the best investment choice for the buyer, but we don't judge.

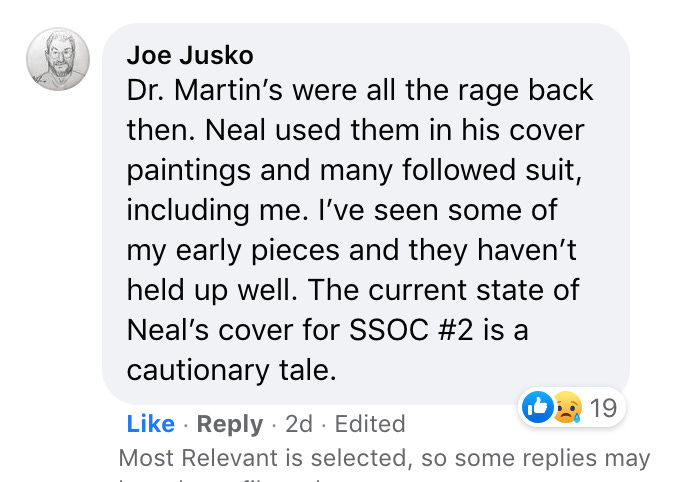

A long discussion about the dangers of using Copics, Dr Martin's Concentrated Watercolors, and other dyes to create permanent art ensued on Facebook.

But hey, we're just professional artists with decades of experience. What do we know?

Do not use dyes to create art you want to last.

There is a new range of Dr Martin's which is permanent: get that instead.

Fine art materials are no more expensive than Copics. Many are even LESS expensive.

And if you choose to keep using Copics, hey, whatever, it's your art's funeral.

Colleen, you absolutely know your stuff about dyes. But you are confusing one point. And many working pros, over the years, also make this mistake. "Non-repro blue" is not really invisible to a camera. For line art reproduction, light blue takes a longer exposure to show up on a negative. So it is fairly easy to drop it out of line art shots. But, if you wanted to capture a page of blue penciled art, you could shoot a halftone and capture all the subtle details. Give it a long enough exposure and you could get a line shot out of it. The negative would be very dusty, but it could be done. In the case of blueline color paintings, the camera sees that blue just fine. The same way it sees the same blue used in the painting. That blueline ends up backing up the black line art when printed, making the black line richer and darker. This is important, since the black ink commonly used in CMYK printing is transparent. Printed without other colors, that black ink appears washed out and faded. My studios, Insight Studios, provided bluelines for all the major and many of the minor publishers up until about 2006, by way of credentials.

Hi Colleen, I used Dr M’s in the seventies and up until I went digital in 2004. I’d done hundreds of colors and they have all kept their brilliance. Only a small number have ever hung on walls for long but they aren’t too worse for the wear unlike those you posted. The rest have been kept out of the light and are in pretty much mint shape. Some are a little discolored in the paper substrate I used for a time, Strathmore Illustration board, with a yellowing. Have you heard of Nicholson’s Peerless Transparent Watercolors? I just found and old box set I got but didn’t use much. Still in good shape. I checked my old Dr’s and more than a few have dried out in the bottles but most are still good. It’s not like I’m going to start using them again even though I have a half full package of Strathmore Bristol cold press two ply. I can pass it all on to my artist grandson Escher. New subscriber here.