When a publisher announces a contract for reprint editions of your book, sometimes it’s good news. Another publisher buys hardcover or foreign rights or limited edition rights, or whatever, you reach a new audience, and there’s a little bit more money in your pocket.

But expanding the audience with reprint editions wasn’t what was happening here.

I wrote of how one day my old publisher had me in the office and bit my head off, told me I had no talent, and then told me to get out of the business.

Mere days later, I was his bestest little artist, like a daughter (not kidding). He loved me and my work, denying everything he had said before. Either he was having a moment or something was up.

Something was up.

The publisher was in financial trouble and had been for years, sinking into debt before I even got there. They had been bought out by their printer some years before because they couldn’t pay their printing bills, and even though the long departed Woman claimed their graphic novel division had more gross revenue than any other division of the company, gross is nothing. Net is everything.

At one point, they had also sunk huge sums of money into a travel guide book scheme fronted by some lady who had a cable TV show that bombed badly. So, their GN division wasn’t the only trade book line that was sinking the company.

My publisher was pissed off because the printer/owner (Walsworth) was pulling the plug on the trade division and he was about to be out of a job. He was not in a good mood, especially where flaky little artists like me were concerned. He’d bet that we would bring in huge bucks with our graphic novels and save his company, and he lost his gamble.

Only a few of the GN’s made any money, and none of them made nearly as much money as it seemed. Their best selling title was often touted as having “millions” of sales and “millions” of fans.

Nope.

Their best selling title had a solid core audience which sold about 17,000 copies per year per volume.

17,000 copies per annum is solid. Any creator would be happy to have that evergreen on their backlist. You can live a comfortable life with a set of books selling like that every single year.

Publishers love backlist too, it’s almost like free money. Sales just churn along without much effort. But this series was nothing like the runaway hit people think it was.

It really doesn’t take very many sales to make bestseller lists either, and I know, I’ve been on the New York Times bestseller list more than once.

But it was (and is) very common for publishers and creators to conflate the size of the sales and audience by adding up every single copy of every single book they ever sold and acting like the cumulative total was the audience reach.

If you had a comic series that sold 75,000 copies per issue, did some reprints, and published some trade paperback collections, and you added all that together, you probably sold 1 million books. That sounds to the average schmoe as if you had one million fans.

But you don’t. You have a core audience of maybe 75,000-100,000 fans, some of whom probably bought multiple editions of the same item. Again, that is very respectable. Any creator would be pleased. But one series selling those numbers can’t fund an entire trade publishing operation for long. And 100,000 sales in 1987 at a big publisher like, say, Marvel Comics would get your book canceled for being too low.

Those were the days.

My own work A Distant Soil has sold roughly 750,000 copies. But the reality is, I never had an audience larger than about 40,000 readers, and most of that was during the self publishing/black and white booms. That’s a good small press sale, most people are never going to hit that number. But 750,000 sales is not 750,000 readers.

Another harsh truth is almost every single indie press yuckster I know of back in the day - with the notable exception of Jeff Smith’s Bone and the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles - watched 80% or more of their audience shrink away as the years went on.

75,000 sales in 1986?

Wish on a star in 2023.

Self Publishing, sort of like Squid Game, only no big money for the survivor. I can’t recall who the guy on the left is, but that is me enveloped by Dave Sim, and Martin Wagner. No idea what happened to that guy.

If you had a handful of books selling nearly 20,000 per volume in 1985, you were making some solid money.

But not enough money to cover the costs on one book after another selling only 2,000 copies. In general, a trade book needs to move 5000 copies just to break even.

You see this happening all the time now, too: some indie press has one or two flagship titles that seem really popular, they get some licensing deals, the company expands, and then it all implodes, and everyone wonders what the hell happened.

Well, it’s basic math.

Some authors had received far larger advances than mine, including one comics artist who was paid $10,000 to produce about a dozen black and white illustrations and a color cover for a classic novel that only sold about 1,000 copies. While I was getting chump change, bigger name creators were getting big advances (that $10,000 advance that creator got for a dozen illustrations, adjusted for inflation is about $30,000 now,) but their books were selling less than mine was. And the loss on that one book would have eaten up a fine chunk of a year’s profits on one of their best-selling titles.

The publisher was unable to figure out how the comics market worked and how to get popular comics creators from the direct market to sell in the retail trade. They also had no luck getting big name science fiction creators to cross over successfully into graphic novels.

In all fairness, the rest of the comics market didn’t really figure all that out for another decade or more, either.

Walsworth had a plan to continue to bring in revenue on those books that were still profitable like mine. Walsworth/Donning was working up a secret deal to sign our contracts over to another publisher, but had no intention of telling any of the authors about this. Only 12 authors were being bought out including me, because we were the only ones bringing in any real dough. I wasn’t making any money on my books, but the publisher sure was. Most of the books were New Age books. I think mine was the only GN that was bought.

However, they had no right to transfer our contract agreements without our permission. Instead of contacting us for permission or to negotiate a contract sale deal, Donning told all of the authors involved that only reprint rights to our books had been sold.

My publisher was glad to see the back of the lousy comic creators he believed had helped ruin his company when we failed to make him really, really rich (he lived the good life anyway, but he wanted a really, really good life), so he blew up at me in the office that day and got it all off his chest. However, when he realized that my book was one of the ones picked up by the reprint licensor, he had to keep me happy so I would continue producing new volumes. A core feature of the secret contract sale was that the creators were going to keep producing new works.

So, the next time he saw me, he was all smiles again. He brightly asked when I would have a new volume ready only days after he had told me to give up art for good. He had not remembered that he had signed all my licensing rights and black and white publishing rights back over to me. “I don’t recall that!” was one of his favorite phrases (right next to “Artists sell themselves so cheap.”)

Walsworth (Donning’s owner) sold my contract to the licensor without letting the licensor know that there were virtually no rights left to buy, because the Donning publisher had simply neglected to let Walsworth know he had signed those rights back to me months earlier. So, one day it was “Get out of publishing!” and the next it was, “I love your work and when are we going to get a new book?”

By then the entire trade line was dismantled. We no longer had editors, an art department or marketing people (I had to deal with the publisher’s wife when I had a question). The authors were baffled. The publisher wasn’t telling us anything. And I was even more confused when I had a chance to speak to the new licensing company (Schiffer). They demanded to know when they would be getting another book from me. I thought this was strange behavior from a reprint licensor. They weren’t my publisher, but they were sure bossing me around like one. They would not tell me anything about the format of my reprint edition or to which market it was being targeted.

The edition of my work that they licensed came out months later and I hit the roof. It was identical in every way to my original publisher’s edition, except for the name of the publisher. This was not a reprint edition, it was a reprint. When I called the licensor trying to find out what the heck was up, he refused to speak to me. My old publisher ignored my letters.

Authors traded information and a class action suit was filed. I was contacted some months later by one of the authors and asked to join the suit. I spoke at length with Harlan Ellison who was also concerned about his editions, but lucky him, no rights to his work were transferred. (They were scared to death of him).

Donning/Walsworth wanted to continue to make revenue on the profitable books without having to spend any more money on their trade division, so they cut this deal with a third party licensor to publish our works and cut the authors out of the revenue stream. Donning would collect half of all revenues on our works from the licensor which dropped our already meager earnings into the toilet.

On A Distant Soil, instead of 10% of cover (when my book sold over the 10,000 copy threshold, I earned up from 8% to 10%), I would now earn 5% on retail sales. On direct sales books, I would now be getting 2.5%. Considering amounts held against returns, for at least a year that meant your earnings were 2.5% retail and 1.25% direct. It was a nightmare for all of the authors.

Since my new book was a $12.95 trade. I’d be getting a whopping 16 cents a copy on all sales in the direct market. So, if my book actually sold 30,000 copies there (NOT) I’d gross all of $4,856 – about enough to pay the colorist, but not enough to pay the letterer, or any other costs…including me. In order to earn out my meager advance within a two year period, I would have to move something like 50,000 copies, assuming at least half of those were sold in the retail trade where I’d get a bigger royalty. Worse yet, even if I did earn out the advance, the take would be eaten up by the cost on the next volume of the book, and the deficit on The Woman’s book.

The misery mine deepens when my publisher began demanding further volumes of A Distant Soil from me and even threatened to sue if I didn’t come up with another GN right away.

Despite the fact that my publisher claimed he had never signed an agreement to release my licensing or black and white publishing rights, I went right ahead with my self publishing adventure, and they didn’t dare sue when I told them they would never get another book out of me (and they didn’t).

When I worked in the publishing office and witnessed their lawsuit against Teh Crazy over the definition of reprint, I knew exactly what reprint edition meant: an edition significantly different from the primary edition so as to be non-competitive but to appeal to a new market.

Now, my publisher was claiming the exact opposite definition through his attorneys: a reprint edition could mean a second printing, a printing no different from the first. The core of their defense was that since (they claimed) they were the only publisher in Virginia (a ridiculous lie) they set the standard for the legal terms of art in the state, and whatever they said was the definition of reprint edition was what the legal definition ought to be.

Their attorneys were very, very belligerent at the deposition, having been told many tales about what a noxious character I was by – you guessed it – The Woman. My old publisher who had dismissed her years previously brought her in to be a character witness against the authors, and she told quite a tale.

They even asked strange questions about several author’s personal beliefs and religion.

Science fiction artist (and fellow author in the lawsuit) David Cherry was fuming when he walked out of that deposition, and he was a former attorney who thought he had seen it all.

It got even nastier when they began grilling me about a story that had appeared in Publishers Weekly. Someone leaked the news about the lawsuit and it was all over the publishing industry. The lawyers really let me have it, certain I had been the one who squealed. I had nothing to do with leaking the story, but since a lawsuit is a matter of public record, I had no idea what they were getting at in trying to make me look like a bad guy for going to the press with the info, especially since I hadn’t.

The publisher claimed that we were conspiring with a former business partner of theirs to take all of our books to the ex-partner’s new publishing company.

This was a multi-million dollar lawsuit, and the publisher hired private detectives to spy on the creators. They even tapped our phones. I noticed weird clicks and buzzing noises on my line every time I made a phone call, and a couple of the other authors said they were hearing weird sounds, too.

I called the phone company and they ran a test. “Do you have another phone line?” they asked. “No, I only have this one phone.”

“Well, there’s someone else on the line.”

There was a loud static noise, a click, and that was the end of that.

I came home one day to find the back porch area looking a bit odd, and some storage boxes in my office appeared to have been moved.

And what do you know, letters between me and David Cherry showed up at the deposition. This was pre-email, so the only way to get these letters was to get the originals in our homes.

The letters were pretty tame, but the publisher’s detectives were trying to prove collusion of some sort, and any connection was, to them, important evidence of a conspiracy.

The only author I really knew and was on good terms with was David Cherry. We stayed friends for years. But the others? Barely knew two of them, and couldn’t name anyone else. And neither David nor I had any relationship with the former business partner, and had not spoken to him since he left the company.

Since I didn’t know the former business partner even had a new company, this was especially confusing to me. The ex-business partner was a New Age enthusiast and published inspirational books, hence the bizarre questions about our spiritual beliefs (a lot of the books involved in the suit were New Age books.)

The ex-partner had been gone from the company for years and I simply didn’t know what the lawyers were trying to get at. Obviously, I was self publishing A Distant Soil, and had not taken it to this former partner’s company.

As I mentioned before, The Woman was Donning’s star surprise witness. She claimed that after I had left Donning I had been unable to forge a career elsewhere.

“No editor works with her twice,” she claimed.

OK.

My attorney picked up a couple of long cardboard boxes containing some of my published works and set them on the table, flipping through stuff I had done for multiple clients from Marvel, to Scholastic, to Disney.

“What the heck, she’s got a stack of credits piled higher than the chair! How can this possibly be?”

I’m paraphrasing.

In the years since I had worked with The Woman, I had produced over 200 published works. Clearly, someone was happy to work with me.

And more than once.

I realize this was all pre-internet, but you’d think one of these paragons of jurisprudence would have done some basic research before we got to the table.

The level of crazy there was just - I mean, freaking bloody hell.

Donning’s lawyers even went so far as to produce letters from a stalker.

When I was a teenager, a former Marvel Comics employee became obsessed with me after seeing my picture in a magazine. I never knew the guy, and I think I only met him, briefly, once.

His face should be in the dictionary under the word “stalker” because he looked like he came out of Central Casting, file under “weirdo”.

Over the next several decades, he wrote me letters, sent gifts, made numerous unwanted phone calls to me and clients, enlisted other people to follow me, call me, send stuff, and to harass me and hit me in public.

Yeah, he did that.

When I worked at the Donning offices, he called almost daily. When I stopped working there, he tracked down comic shops in the area and started calling them.

Basically, he did everything he could to get my attention and interfere with my life.

He’s been arrested a few times and been in and out of care. The experience was chronicled on one of those Discovery ID shows, but they edited it heavily, I think, trying to avoid trouble with Marvel’s lawyers (and for what it’s worth, I’ve never considered Marvel responsible for his behavior, they’d fired him in the mid-1970’s and he only had a few freelance credits after that).

Regardless, the Stalked: Someone’s Watching episode was not only misleading, it took a lot of tooth out of the worst of the experience.

Whatever.

But, I kid you not, when I was in that deposition, those lawyers pulled out a file Donning had kept of letters the stalker had sent them about me.

And here his lawyers wanted to use these missives of crazy in court against me. His opinions about my work, his “inside information” about my life, how he thought the lawsuit should go. He wanted to give his “expert testimony”. It was nuts.

I know scummy things happen in court, but that was not just low, it was stupid.

But, finally, we get to the fun part when they asked me to define reprint and reprint edition, the crux of the lawsuit.

I told them what I knew reprint edition to be. They became very angry and repeatedly grilled me to define it over and over. Donning’s attorney snapped that he wanted to know just how I could possibly know the definition of those mysterious terms that must somehow be beyond my ken - reprint and reprint edition.

The Woman had led the lawyers to believe that I was too dimwitted to know what I was doing and too talentless to make it in publishing - and that was some kind of wishful thinking on her part, boy howdy.

And funny, too, because if that’s what she thought, why the heck did she sign me on at Donning in the first place?

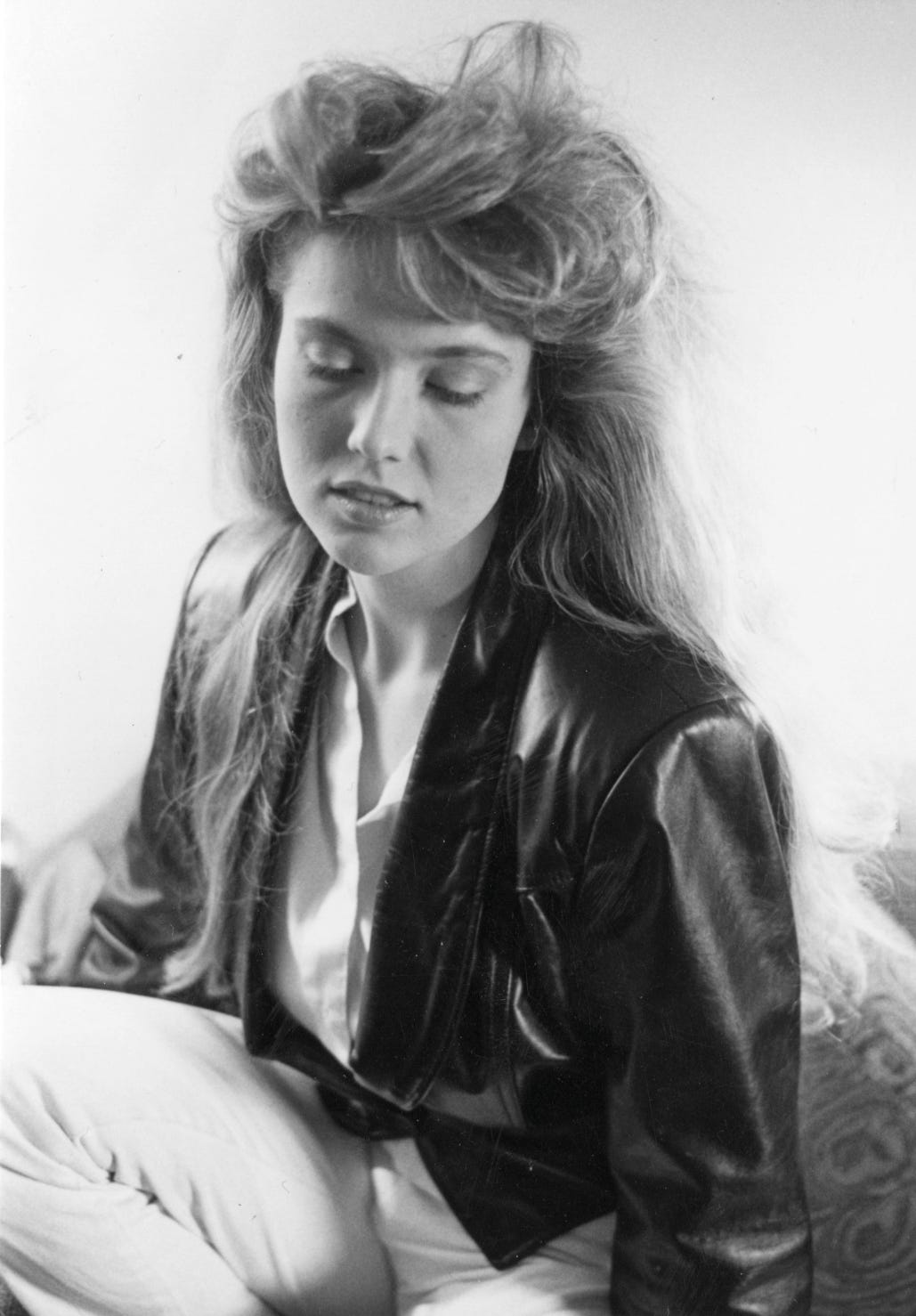

The little woman is delicately perplexed.

So the lawyers were expecting, I dunno, maybe a little blond tartlet who drew stick figures, I guess.

But I pulled a mind scramble on them. I opened my mouth and talked.

The wit and wisdom of Edgar Frog.

Actually, I didn’t talk much at first, I sort of went “Uh hunh”, and “Yeah”, and mumbled for awhile because I could see it was pissing off the attorneys and the court stenographer would have issues with my grunts, and this gave me petty pleasure.

Anyway, I finally said the Donning publisher told me what reprint edition meant.

The guy grilling me went a little pale and then asked how I came to talk to the publisher about it.

I stated that this publisher had sued authors over the definition of reprint and had asked me to recruit people from New York publishing houses to testify for them in their lawsuits years earlier.

You know. The one on file with the court.

So that’s how I knew, see.

This brought the house down.

When the deposition was over, my lawyer looked at me and said, “We just won.”

I knew I signed a bad contract and had been misled by this publisher, and the only way to get out of the situation was to learn how not to make the mistakes I had made before, and to learn what my publisher’s weaknesses were. My publisher had so little respect for authors and artists – and for me in particular – it would never have occurred to him that I might actually be paying attention and gleaning useful information when I spent months and months going over documents, reviewing sales charts, and interviewing company employees while I was working for no pay.

I mean, duh. What the heck did he think I was sticking around there for?

They didn’t even have free coffee and donuts.

Donning had mistaken my patience for passivity. Since I first encountered them when I was no more than 16 years old, it was understandable that they would severely underestimate me, but this lousy (not to mention sloppy) contract swindle was ample evidence of Donning’s contempt for all the authors and artists.

We returned the favor by giving them exactly what he deserved.

The authors didn’t have to endure a grueling lawsuit with big legal fees (though in retrospect, we’d have probably gotten a lot more money, considering the copyright issues involved). The publisher’s prior court case on file with the Circuit Court was enough to hang them, and I knew about it because years before, the publisher had taken advantage of me, had had me work for months as an unpaid office gofer, and I had gotten the goods to kick them in the nards years later with everything I learned.

You know what they say about dishes best served cold.

Yum. Yum.

Revenge was pretty sweet, especially when it came in the form of a big legal settlement (which I can’t reveal – sorry). Of all the authors, because of the track record I gained in publishing over the ensuing years, I could prove an even better professional reputation and more damages than almost anyone else involved in the suit. I got the second highest settlement.

I was told that the Donning publisher was incandescent with rage and screamed at the attorneys over the size of the settlement paid to me, in particular.

Gosh.

I got enough money to make up for a lot. Amortized over the total number of pages I had done on the series, I had now received a very fair page rate for my work. I was well satisfied.

But I was about to get even more satisfaction out of it all.

I called Harlan to let him know how things had turned out and he gave me some lovely advice about remaindered books. Since I was self publishing, I had accounts in place to sell my own work to bookstores.

As part of my settlement deal with Donning, they had one year to liquidate the remaining inventory of my books.

Fortunately for me, they were so magnificently incompetent they sold absolutely nothing.

Not one copy.

After one year, they offered them to me.

Remaindered books are the savvy author’s happy little secret stash. If you’ve got some cash, and your publisher determines that there is no longer a market for your work, they will sell it to remainder buyers at massive volume discounts. A $15 book may get a price of only 50 cents a copy if the buyer agrees to take them in sufficient quantity.

Harlan had been buying out his book stocks for years and did a snappy mail order business selling autographed copies of his works. Moreover, he always made sure his contracts required that any books be remaindered to him first before they were offered to anyone else.

Sometimes this meant buying out a small stock of no more than 50 or 100 books for an author, but it can be very good extra money selling them at shows and autograph signings for cover price. This is how a lot of authors make extra money on their books.

In my case, Donning had thousands of books I worked on, especially since they had about 20,000 copies of the dog - I mean, book - I had illustrated for The Woman.

They offered me a deal where I could buy out the remaining copies of A Distant Soil at discounts that would increase as I bought more copies. But to get the best discount, I would have to buy several thousand copies of the book I did with The Woman.

I not only sold out the entire inventory of A Distant Soil that I had purchased at only 35 cents a copy, but I had also managed to sell thousands of copies of the book I had done with The Woman. It took several years, and some marketing hijinks such as selling autographed copies and including promo prints from my other works, but I pulled it off in the end. I went from thinking I would never see another penny on that book to making at least $3 per copy sold. The Woman’s GN did not do nearly so well as A Distant Soil and I ended up having to trash some unsold copies rather than continue to pay for warehouse space for them. But no worries. I made a handsome profit on them.

In the end, I made a nice $50,000 (even nicer when you adjust that to current value for inflation) on the total remainder deal for all my projects (in addition to my hefty settlement), all money that my ex publisher could have made for themselves with very little time and effort (this is a perfect example of why their trade division went out of business). I earned enough money to keep my self publishing operation running in the black for a while longer when the comics market went belly up in the mid-1990’s. Those profits kept me afloat until I later signed a contract with Image.

When The Woman saw that I was selling copies of the book I illustrated for her, she went mad, believing I had reprinted the book and stolen her copyright. She sent me an eight page letter threatening to sue. It would never have occurred to her that I had just bought them directly from the old publisher, something she could have easily done for herself if she had had any imagination and ingenuity at all. I made very good money on a project that initially kept me in poverty and she got nothing but sour grapes. My lawyer sent her packing when she came calling (more on this later, too).

Once, I told some A Distant Soil fans how I had bought my books and sold them to people for more than I paid for them. They were furious that I didn’t sell my books to all my fans at my cost. How greedy I must be!

This, of course, is the kind of thinking that makes people very, very bad at business. Without profit, you do not pay your mortgage, electric bill, food bill, etc. Profits on these books paid bills when I had no other income some years later. Moreover, there is cost involved in shipping books and warehousing them. And since I had had to spend some years in poverty because of these books, I think I was more than entitled to make money on them later.

So, if anyone thinks it is rotten for an author to actually make a profit on their book…I don’t know what to say except one day I hope you will make Darwin proud.

And for an extra special irony moment: after the trade division was long gone, Donning contacted me to ask how they could sell more of their remaining inventory of other people’s graphic novels into the direct market. They had thousands of books in their warehouse. Including books drawn by Tim Sale, which would have been incredibly easy to market and move.

A decade later, they had still not figured out how the direct market worked. Yet they had come to me, an author to whom they had paid a settlement, to figure it out.

Oh well, no hard feelings.

Next, the absolutely bizarre and 100% true 20-years-in-the-making-sequel.

I just love it when good people have a big win. I equally love it when people who are underestimated win against condescending shits.

This was the article I was hunting, and so glad I found it! Remaindered books was the term I couldn't recall, although the concept and the wisdom inherent stuck in my mind.

The artist I collaborate with and I submitted our work to a publisher, and as I am still hunting a lawyer, I can at least get great advice from someone who has been there. Again, thank you so much for sharing your experiences. For those of us wanting to get into the pool, it's amazing to read of your experiences and learn from them. So heartfelt thanks from both of us!