In 2008, Jeff Smith of Bone fame asked me to write a guest column about my memories of the early 1990's self publishing movement for his blog.

Young whipper-snappers didn't even know there was a self publishing movement before the internet.

This is my entire two-part column rescued from internet obscurity. For awhile, it was also lost on Jeff's blog, but I think he's got it back up again.

I didn't name the publishers Kelly Freas didn't like in the article, but I guess it's not hard to figure out anyway, so there it is.

And now, a walk through self publishing memory lane, parts I and II in one handy post.

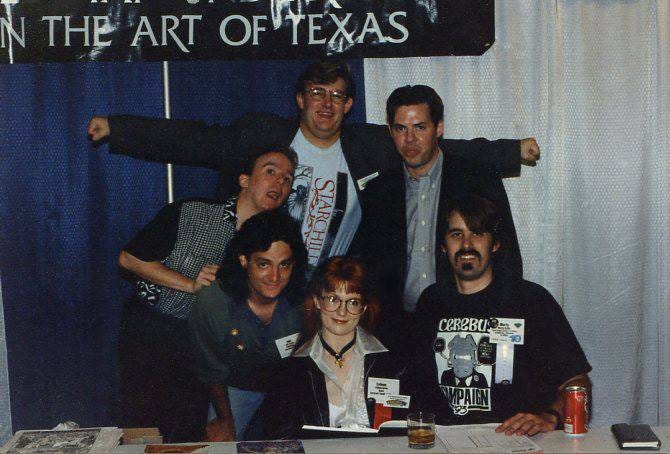

Self publishing was kind of cool, once. With Jeff Smith, Dave Sim, Martin Wagner and Owen, I’m sorry I have no idea how took this pic and who the other guy is. But what I do know is for a few years there the lines at our autograph booths ran two hours long. Heady times.

For a while, self publishing comics was the coolest of all possible cool things to do. Retailers and fans waited in long lines to get the autographs of the core self publishing movement creators. The party seemed like it would never end. We spent months out of every year on the road promoting work, signing autographs, holding “bar cons” that lasted until 5 AM, doing free sketches for retailers and fans until our hands swelled up, and we lost our voices or, in my case, passed out cold from low blood sugar.

It was exhausting and exhilarating. We were supportive and competitive. The stress was unbelievable. The extremes of our lifestyles made us cranky and sick, hilarious and energetic, Tourettes bipolar.

Contrast the solitary, long hours we spent drawing comics in our homes and studios with the swarms of attention and loud parties of the convention scene – I’m surprised we didn’t all end up in the loony bin. We lived like rock stars on the road, and then went back home and, in my case, slept in my only real piece of furniture – a chair. People assumed we were all filthy rich, and while there was money coming in, it went out just as fast, reinvested into new books, inventory, and promotion.

It all started with a small band of creators who, for the most part, either wouldn’t or couldn’t be published elsewhere. Jeff Smith, knowing nothing about the comics scene, sprang full grown from the head of Zeus. He was The Complete Cartoonist and wowed everybody. Dave Sim was the old man of the group and styled himself The Guru. James Owen was The Salesman. Martin Wagner, The Huckster. Larry Marder, The Machiavellian. Steve Bissette was Mr. Sensitive. Rick Veitch, The Dreamer. Me, I was just The Girl. This wacky crowd of self publishers broke all the rules.

Wild rumors circulated about drug use and romances: I saw none of that. There was no time for goofing around. We worked seven-day weeks, and went for months (or years) without breaks.

At some shows, Dave Sim provided the core self publishers with limo service, as well as other ruffles and flourishes that supported a successful image. All base expenses were our individual responsibility, but limousine service made us look good, and The Guru of self publishing wanted to look good. Making self publishing look good was more important than the objective reality that self publishing was unlikely to be good for almost everyone trying to do it.

When I got home after tooling around in a limo, I didn’t have enough money to buy a car. The public never saw the trips to the Goodwill to buy a decent outfit to wear, anything to save the money to get that next issue published. I reinvested more than $50,000 a year of my income back into my work. Sometimes there was a nice sum left after all that. Sometimes there wasn’t.

Most people never made a dime of profit self publishing. More lost a small fortune. Some lost big. Caught up in the excitement and promise of big money and convention fame, they heaped scorn on anyone who tried to warn them. A few of us (like me) even loaned promising creators money. And we never saw these people (or our cash) ever again.

Some of these wannabes weren’t in it to fulfill their creative urge. To them, self publishing looked like an easy way to make a buck. Jeff used to call these efforts “random acts of self publishing”. The poor quality of work being churned out by legions of wannabes began to turn retailers off, and sales plummeted. Few could get established without the original self publishing creator’s first mover advantage: when there were 7 self publishers, it was easy to get noticed. When there were 700, not so simple.

Self publishing was a major source of income for me for nearly six years. But in 1995, the direct comics market imploded and most of the comics distributors went bankrupt.

Anyone can self publish on the web now. All of the computer equipment and webspace one might need for a year is roughly the same as the cost of printing one issue of a comic book. You self publish whenever you write on a blog. It’s normal, and in some jobs, it’s expected. Creators are now actively encouraged by their publishers to promote their work on blogs. Saves the publisher the hassle of paying a marketing department.

But when we were wee tots, self publishing was radical, it was a huge financial risk, and only crackpots who couldn’t get published anywhere else did it, and only people out of their minds with ego promoted their own work. There was no internet to speak of.

I started self publishing projects when I was about 12 years old, stapling together zines, making lithographs of prints and selling them at conventions. I self published my comic book series A Distant Soil for about six years before I threw in the towel and moved to Image Comics. So, there are my creds.

When I was still a zygote, I was introduced to self published comics via the work of Jack Katz whose First Kingdom predated the better known Cerebus and Elfquest. Friends in SF fandom had brought copies to a club meeting. Even though I was impressed by what I saw, like most people, I assumed self publishing was code for “Can’t get a real publisher.”

Self published comics were around way before my time. Early efforts include works by Gil Kane dating back to 1968. Our big “self publishing movement” didn’t start until the early 1990’s. Those that came before didn’t get much press. And they usually didn’t meet with much success, with the obvious exception of the worldwide media hit The Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (1984).

When I was fifteen-years-old, I met Kelly and Polly Freas who had started their own company Greenswamp Press. Kelly is probably best known to comics fans as the Alfred E. Neuman artist for MAD magazine. Here was the top SF artist in the world producing beautiful work at his own company run from his home, with inventory stored in the barn. According to Kelly, Elfquest was originally supposed to be published at his Greenswamp Press label, until the creators decided to go it alone. I worked as Kelly Freas’s assistant in the 1980’s. Kelly created the Starblaze label at a small, local publisher, which went on to publish a few early graphic novels, including work of mine.

I was surrounded by people who were self publishing, but as a teen I didn’t think I would have much luck publishing my own work. Anxious to go pro, when publishers offered me contracts, I signed up. Surely, working for a real publisher would be better than whatever I could achieve self publishing!

Well, no.

On books that sold tens of thousands of copies, I never made more than minimum wage, and sometimes didn’t get paid at all. In the 1980’s, I was landing my first mainstream comics work, but even so, my page rates were among the worst in the business. I could not make more than $10,000 a year working 80 hour weeks. The mainstream wasn’t paying me big bucks, but at least they paid me. The small press sometimes paid nothing.

I didn’t understand why my small press clients had money to buy thousands of dollars worth of original art, ivory knickknacks, and BMW’s, when they could not pay the creators that produced the income. To add injury to injury, I ended up in several lawsuits over my work as well. So much for creator owned comics! I was the creator, so why was I forced to fight for my copyright and trademark?

Kelly Freas later confessed he had been disappointed I had gone with a small publisher he didn’t like with my work A Distant Soil. He would have published it himself, or even helped me to do it. What a missed opportunity!

It was time to give self publishing some serious thought. Most of the people I encountered in the small press had no experience, no training, no creds whatsoever, yet they hung out a business sign, and promoted themselves as “real” publishers. Why were any of these people more qualified than me or any other cartoonist? Running a company out of their basement made them publishers, qualified to make more money on my own work than I did? Why were they more legitimate than someone who published their own work? Because their basement was bigger? They had a bigger wallet? Bigger ego? Greater need for a BMW? What?

If I was going to be published by amateurs, I might as well do it myself.

Cerebus creator Dave Sim (whom I had met after A Distant Soil was first published) and I had several arguments over the possibility of my self publishing, with his view being that I should “Just do it!” and my response “With what money?” falling on deaf ears. We parted ways and didn’t speak for years while I planned to publish my way.

Me, cross selling my mainstream work with my self published work at shows with mixed results. Someone was selling this autographed pic of me on ebay, so I posted it here. Fair game, bro.

I drew more comics for Marvel and DC, and with the settlement money from one of my publishers over rights to A Distant Soil combined with a small loan (and looking back on this, I did not take out that loan until a couple of years after I started self publishing, but whatevs, it was a cash flow glitch loan,) I finally had enough cash to get my A Distant Soil comic printed myself.

I had never worked with a printer before, had meager layout and paste up ability, did not own a computer, and could not balance my checkbook. I was 20-ish and had no business skills, and only one-year’s experience working as an unpaid gopher in a trade publishing house. All of which made me about as qualified to publish as anyone who had ever published my work in the small press. After diligently studying every word trade book self publishing guru Dan Poynter ever printed, I was able to get my comic out.

My local printer knew they were dealing with a rube and padded my bill. They let my books sit unpacked and unshipped for two weeks. I personally packed and shipped all 8,000 orders in a desperate bid to make the Diamond Distributor deadline. Realizing my printer was a yutz, I found another and asked for my negatives back. I got them after I threw a screaming fit in the office in full view of a bunch of their customers. They were in such a rush to shut me up and return the client folder which contained my negatives, that they neglected to remove their internal correspondence file, the one containing the memos detailing how they had padded my bill.

That wasn’t a great beginning.

However, my book quickly sold out its print run of nearly 10,000 copies, and I realized I had made more money on that comic than in personal income in almost every single year I had been working for “real” publishers.

I was told that self publishing would get me blacklisted at Marvel and DC. Didn’t happen. If anything, my cred in the industry improved markedly.

The self publishers published books that should not have sold at all. Our works were too cartoony, too girly, too esoteric, too whatever. They sold good numbers, regardless. We had no competition. Whatever we did, there was nothing else like it coming from Marvel or DC, and there were few small press companies that published anything that wasn’t a rehash of mainstream comic trends.

We reprinted our comics whenever they sold out risking the ire of the retailers who complained we were killing their back issue sales. Now, reprinting comics is business as usual.

Conventions had a lot to say about what creators could do at their shows, but that soon changed. Back in the day, attending artists could sell nothing but original art. If you self published, you could not sell your own books at a show, regardless of the fact that many retailers did not carry them. We raised a stink over this unfair practice, and now it is the norm for creators to sell their own books at conventions.

We produced graphic novels that we kept in stock with multiple reprints, further risking the ire of retailers who were convinced GN’s would hurt back issue values.

We campaigned to get our books into retail stores and libraries. This effort took a decade of work. My first Book Expo trade show was such a bad experience my self-esteem shriveled to a micron. It was four days of junior high school, only instead of getting snubbed by cheerleaders, I got abused by retailers and librarians.

Later, while attending the Book Expo with Image Comics – and after having spent years sending one package of graphic novel samples after another to disinterested distributors – librarians were begging for graphic novels, declaring them the books that tempt the “reluctant reader”. Jim Valentino, who had also self published back in the Dark Ages and helped to found the uber-self publishing group known as Image Comics, worked hard to get Image books into new these new markets.

Just a few months back, Bob Wayne and Paul Levitz of DC Comics floored me when they declared, “You guys were the first. You showed us the way.” We traded horror stories of the sad bad days when no one wanted graphic novels. Bob Wayne and I compared psychic scars that would have needed a decade of therapy had we not gotten the last laugh instead.

Big in Japan. Or not. At the Tezuka Productions offices in Japan, with Jeff Smith, Nicole Hollander, Jules Feiffer, Denys Cowan, Vijaya Iyer, Fred Schodt, my mom, the president of Tezuka Productions Takayuki Matsutani, and a face or two I can’t recall. Someone wrote this unauthorized bio of me claiming this event made me “wildly popular in Japan”. I am not and have never been wildly popular in Japan. None of us were. But whatever.

The self publishers weren’t the first to make graphic novels, or the first to reprint our comics. When I was a little girl, my first comic GN was a Prince Valiant volume that I had bought from a Scholastic catalogue that had been provided by my school (it was originally published by Nostalgia Press, but distributed by Scholastic.) This was a novel length, continuing story in book form being made available to school children through a major book publishing house catalogue. And later, Samuel R. Delaney/Howard Chaykin’s Empire was a full color, original science fiction graphic novel that I found at my local library. The first graphic novel I saw for sale in a major bookstore was the adaptation of the movie Alien.

Every single thing self publishers set out to do had already been done, but almost everyone had forgotten about it.

Years later, no major comics publisher was able to or willing to try many of these things, treat their comics as books, keep their backlist in print, and get their books into retail stores and libraries, and to produce graphic novels with major trade book publishers.

Nimble little self publishers were willing to try anything, and could change their marketing plans in a moment.

It would take years for Scholastic – the company that had brought me Prince Valiant as a little girl – to latch on to Bone. Jeff Smith’s Bone is the ultimate example of industry-friendly, kid-friendly, library-friendly, bookstore-friendly, everything-a-distributor-ever-wanted book that sells like mad, and if he hadn’t self published it, it’s likely no one else would have.

Self publishing put the work first. Books sold because of what was between the covers, not because of a connection to product (not that there’s anything wrong with that.) Many a cartoonist got the shock of their life when they self published, only to realize they didn’t have very many fans. Their readers were Catwoman fans, or Spiderman fans. Without the sales guarantee provided by the product with which they associated themselves, their work was largely ignored. Many were anxious to join the self publishing circus, and got nothing out of it but printer bills and a storage shed full of unsold comics. Humility rarely followed. Some decided that the sales snub was a sign that the indy comics crowd was dissing them for being “mainstream”.

Eventually, dogma crept into the self publishing movement. If you didn’t self publish, you were a sell out. Self publishing became more important than the work, which was not an idea some of us were trying to promote. When creators like me decided to run off with a publisher, the more inflexible enthusiasts were virulent in their disapproval, insulting us with colorful language, declaring that our antecedents were wanton canines.

For my part, self publishing has never been about getting “in print”. Anyone can get “in print” the minute they write on a blog or go to Kinkos copies and run off 50 copies of a zine. Being in print is not important. Being published well is.

I remember telling fans I could make more money self publishing A Distant Soil than I could drawing The Silver Surfer for Marvel. They thought I was bragging. People assumed that if you worked for a big publisher, you must be making big bucks. And if you made more money self publishing, you must be rich. But my income working for publishers was near minimum wage – sometimes lower. Self publishing ensured that I made decent money for my efforts. It would be nearly a decade before my income from “real” publishers exceeded what I could earn self publishing my comic at its sales peak.

Of course, that all came to an end with the crash of ‘95. Even though I lost my cash wad over the dark days of the late 1990’s, I learned more when publishing myself than I had in ten years of working on nearly 100 projects for “real” publishers. I learned more about my responsibilities as a creator – why timeliness isn’t just about editors being mean to hapless creators. I learned to be more sympathetic to my clients because I understand about cash flow from personal experience! And I understand when clients are BS-ing me about the costs of a project, and when they can really afford to give me a better rate, or move a deadline.

And after the smoke cleared, I went to Image Comics.This is around 2002 or 2003. Can’t recall. Here is Neil Gaiman and Frank Miller with a page of my original art from the graphic novel Orbiter, written by Warren Ellis, which came from DC Comic’s Vertigo division. Heck, I work with everybody, why not.

I learned about zoning, studio insurance, and business licenses, the technical matters that follow when you are running your own business. Few aspiring self publishers wanted to deal with these core issues. Who cares about technical matters when you just want to make a comic? Self publishing is a key person business, the riskiest kind of business. Few wannabes understood that this meant no vacation, no sick days, no benefits, and no time off you don’t pay for out of your own pocket.

Self publishers today – with blogs, web comics, and print on demand – don’t have to worry about the high cost of self publishing like we did, printing lots of back stock, storing inventory, shipping and promotion. You can put your merchandise up at Café Press, you can print only one book at a time, you can get extra dough from advertising with Google, you can get people to put a tip jar on your blog, you can advertise yourself by chatting on message boards.

For many, the choice to self publish isn’t a question of getting to do the stories you want to do. You don’t need to be published to write or draw anything. Self publishing means writing or drawing anything you want and getting it seen, which has absolutely nothing to do with your innate desire to create. Wondering what other people will think of your work – and sincerely hoping they will pay for it – is another matter entirely.

Now, with web publishing, the financial investment required to self publish has made it possible for almost anyone with even a modest amount of cash to afford to get their work seen. You can publish only a page a week and still keep your readers satisfied. You don’t have to sink $50,000 per annum into your dream project to self publish.

Conversely, there’s still no guarantee that you’ll ever make any money. But then, there never was.

Print self publishing is the one thing every artist should try, and every artist should avoid. It’s fun and horrible, it’s a money pit, it’s the road to riches, it’s the best learning experience you will ever have discovering that you are behind the bell curve six days after you get started.

Fiction writer, Chuck Wendig, has referred to fiction self-publishing as "the shit volcano." It's always erupting. There are some good things in there. But lots and lots of shit.

Thanks, Colleen. Interesting photos.