In the 1950’s and 1960’s, Walter Keane was famous for his paintings of big-eyed, weeping children. The paintings look a good deal like manga art to me.

© Margaret Keane

The Keane paintings became popular on the West Coast about the same time shoujo manga was taking off in Japan. I’ve often wondered if Keane Kids made their way across the Pacific and infected the shoujo manga scene, or vice versa.

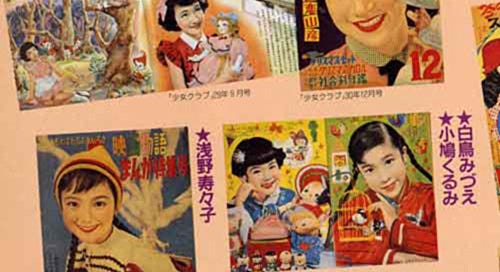

Many early shoujo manga didn’t have the big eyes we now think of as a manga staple. The earliest magazines for young girls generally featured heavily illustrated prose which showed a Western art influence, and had photo covers.

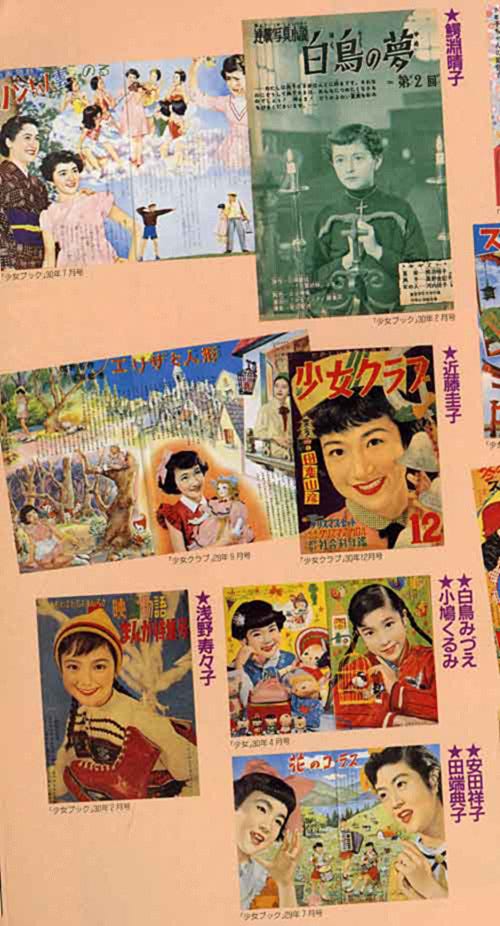

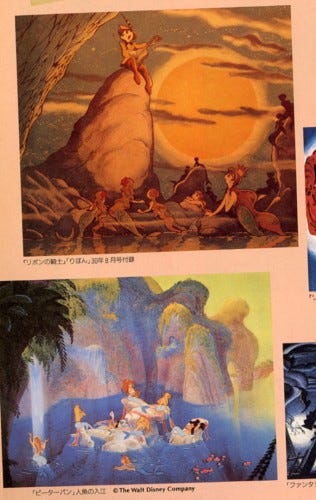

Disney art was the biggest influence on the big-eyed manga look. Osamu Tezuka, the God of Comics, acknowledged this. Later, Disney was heavily “influenced” by Tezuka, most notably on the film The Lion King (but that’s another matter entirely.)

It’s probable that Western cartoon art influenced both manga and the Keane look simultaneously, resulting in a kawaii (cute) look with similar appeal for each culture.

Here’s an article from a book on the history of shoujo manga which mentions the development of Tezuka’s art and the influence of Disney. The top image is from an early anime, and the bottom from a Disney film.

© Tezuka Productions

@ Walt Disney Productions

After Tezuka’s Princess Knight, first published in the 1950’s, shoujo manga was dominated by the big-eye look. Princess Knight is considered by many to be the first true shoujo manga, and it established the look and feel of girl’s comics for decades to come.

While I was not able to find any sources that directly linked Keane to the development of manga, some contemporary artists, such as Reiko Sakurai, openly embrace the Keane appeal.

© Reiko Sakurai

This essay on Miyazaki’s Nausicaa touches on the Keane look, mentions that it is “analogous” to manga, but does not call it an influence.

While it is easy to understand why kawaii images are popular with young children, the reason they are appealing to teens and adults is puzzling to some. The rise of uber-cute is, possibly, a rebellion against female empowerment, or even sexual development. Young teens embody the safety of childhood and the power of adult sexuality simultaneously.

Reassuring images of childlike females proliferate in manga, even when masquerading as a girl power construct.

The paradox of girl power is that girl power focuses on empowering femininity, but restricts itself to patriarchal constructs of what it means to be feminine. The primary restrictions of girl power in patriarchy are the body type favored within the girl power construct, the style of representation, including clothing styles that are appropriate for girl power practitioners, and the constant stereotyping of hyperfeminity and youth. Girl power suggests a means for personal empowerment and independence to the practitioner, especially in terms of personal pleasure. However, the nature of girl power prevents the practitioner from fully developing an independent nature. The girl power body itself is a site of negotiation between these contradictory values.

From the essay "Young Females as Super Heroes: Superheroines in the Animated Sailor Moon" by Victoria Newsom.

Craig McCracken, creator of Powerpuff Girls, is said to have been inspired by Keane kids when developing the look of the cartoon, which also seems to owe a lot to anime/manga.

Power Puff Girls © Cartoon Network

When I was doing consulting work for Bandai, the marketing folks for Sailor Moon wondered why Cartoon Network execs told them that Sailor Moon could not be more popular. Bandai was informed the cute, cartoony, big-eyed girl character designs were unattractive to Americans. I just happened to have a copy of The Licensing Book (an industry magazine) with me at a business dinner, and on the back cover was a huge ad for Powerpuff Girls. The Bandai exec’s eyes got big too there for a minute.

It seemed obvious that a lousy time slot had a lot more to do with Sailor Moon ratings than big eyes.

Sailor Moon got the last laugh in the end, but whatever.

While big-eyed weeping children hardly seem a source for female empowerment, the backstage saga of the Keane kids is a real life girl power tale, though perhaps more in a second wave feminism sense, as defined in the above article on Sailor Moon.

The famous divorce trial of Walter Keane and his wife revealed that the true artist behind the sad-eyed tots was actually Margaret Keane, who sued her husband for credit for her works.

At the trial, Margaret challenged her husband to sit in court and paint. He showed up with his arm in a sling, claiming he had a hurt shoulder and was unable to create. Margaret sat down and painted a Keane original before the judge and jury, which awarded her all rights to her work.

“It had been going on for two years by the time I found out he was telling people he was the artist. And by then, it was hard to change everything. Plus he said he’d learn to paint if I’d teach him, and I wanted to believe him.”

Back in the day, it was not uncommon for women creators to take male names or hide behind a male partner who took all credit. Mr. Keane was, by many accounts, a huckster who then battled Margaret Keane in court for a decade in an effort to seal the steal on her work.

Perhaps marriage to this man was the inspiration for the miserable kids in those paintings. After the divorce, many of the Keane kids wept no more. Her later works depict big-eyed, softly smiling faces. Here, a Keane kid looks happy to be dressed in a kimono.

© Margaret Keane

Walter Keane, who, apparently, had no discernable talent, had to ride his wife’s coattails in order to achieve the recognition he could not earn for himself. Keane took credit for the work, in part, because he believed that it was his salesmanship which made the paintings popular. Be that as it may, he still didn’t paint them, and Margaret Keane continued to enjoy success decades after she dumped her husband.

I recall someone of this ilk saying, “If you want to get revenge on someone, steal their idea and exploit the crap out of it.” Perhaps resentment and envy toward his wife were as powerful as greed in Walter Keane’s case.

Walter Keane’s son (by another wife), photographer Sascha Keane, was, until recently, posting articles to his website giving his father full credit for the Keane paintings with barely a mention of Margaret Keane. However, Sascha Keane’s website is now down.

The Life magazine article linked there has a particularly galling quote:

Margaret, it is true, paints eyes a little like those for which her husband is famous. But hers are not so big and belong as unvaryingly to nubile girls as his belong to what appear to be war waifs.

You know, if the little woman paints it, it’s just not quite as good.

Interesting that so many female creators of my acquaintance (and, well, me) have similar problems with men imposing themselves on their work. Even J.K. Rowling’s ex-husband tried to claim he was central to the creation of Harry Potter, and had personally edited the manuscript. In fact, they were married for less than two years, and during that time she had yet to create Harry Potter.

This creativity assimilation happens to men too, but the social dynamics of the experience differ, one assumes. How many works of art throughout history were the works of women whose accomplishments were usurped entirely by men in times when divorce and redress in court were not available to these women?

The issue is not whether one likes the work of Margaret Keane: the issue is that the work is hers, and her own husband tried to steal all the credit for it.

This article was originally written in 2009, rescued and updated from my old blog.

Regarding Margaret Keane and her husband usurping her credits -- even though I hope it happens less these days that husbands -- or "connected" partners -- try to take credit for a female artist's works, I do wonder sometimes whether there is more involved in the occurrence than just the "social norms" of the past where the works of the "little woman" were devalued. I think that psychological factors and emotional ones can come into it as well.

I've been in a situation where I basically subverted my own professional ambitions so as not to ... well, outshine the person I was in a relationship with. It wasn't a situation where he was attempting to take credit for my work, but my interests were far more wide-ranging than his, and so I curbed myself in for the sake of "his comfort." What can I say -- I was smitten. It was a good thing the relationship did not work out, that is, not a full entanglement. I don't think I would have been able to continue paring down my own creative interests just for his comfort. As it was, I was beginning to chafe at the self-imposed restrictions I had built into the situation.

So, I think that sometimes in the past, women have quietly let their work be usurped in spite of their inner creative drive, just to keep the seeming haven of the relationship.

But in the end, it does boil down to the necessity of being true to oneself, doesn't it? Or as the pompous Polonius says in HAMLET: "to thine own self be true, And it must follow, as the night the day, Thou canst not then be false to any" one (well, of course, good ole Shakes wrote "man", but it is a universal truth).