CHIVALRY: From Illuminated Manuscripts to Comics

The Secret Language of Neil Gaiman's CHIVALRY.

One of the many reasons I wanted to adapt Neil Gaiman's Chivalry into graphic novel form was to create a comic as a bridge and commentary re: comics and illuminated manuscripts.

We're often told that the first comic was Action Comics #1 featuring Superman, a collection of Superman comic strips that morphed into comic books as an art form.

Sequential art predates Action Comics #1.

Action Comics popularized sequential art book storytelling that had already appeared in other forms in fits and starts throughout history. Comic books didn't take off as a popular medium for several reasons, not least of which was the necessary printing process hadn't been invented yet and it's hard to popularize - and commercialize - something most people can never see.

You find sequential art in cave paintings and in Egyptian hieroglyphics. I've read that comics (manga) were invented by the Japanese in 12th century scrolls.

And sequential art appears over and over again in Western art going back well over 1000 years, and in book form at least 1100 years ago.

The most obvious example of early sequential art in Western art - as a complete narrative in sequence - is the Bayeux Tapestry.

At 230 feet long, this embroidered length of cloth was likely commissioned around the year 1070 by Bishop Odo, brother of William the Conqueror. It depicts the Battle of Hastings in 1066 and the invasion of England by the Normans. (The tapestry was made in England, not in France, but it is called the Bayeux tapestry because that's where it is now.)

Imagine what a task it was to embroider this thing. Whew. And you thought it was hard learning Photoshop.

This work of art is important in the history of sequential narrative, but the Norman invasion is also important to the legend of King Arthur - and another important English legend - for reasons we'll get into later.

It's complicated.

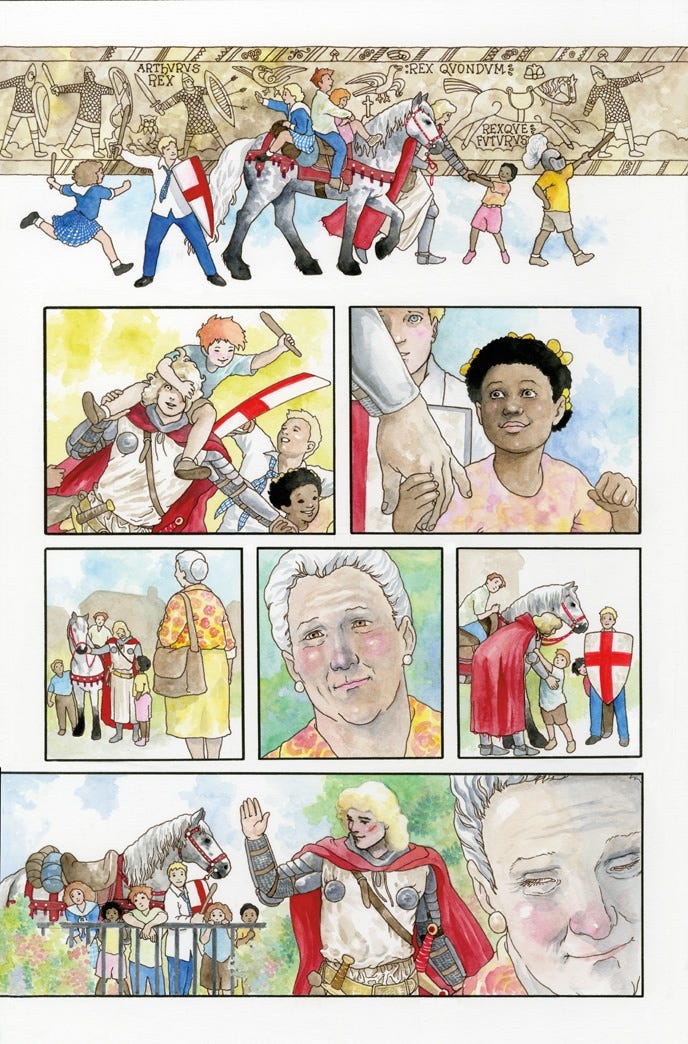

All this is why you see this art in the background of this page of Chivalry.

Using the Romanesque art style of the tapestry in panel 1, I've added the Latin phrase "Rex Quondam, Rexque Futurus" - "The Once and Future King", the final words of Sir Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur as inscribed on King Arthur's tomb, and the title of T.H. White's famous Arthurian novel. (Yes, I know I’ve misspelled Quondam on the original art here, that’s what second printings are for.)

My original intention was to draw this Bayeux Tapestry scene out and juxtapose it with shots of Galaad interacting with the children, but the two page sequence I imagined didn't really work as well in reality as it did in my head.

Foremost among my concerns was that the tapestry reference might be too obscure for most readers. I wanted to weave the visual meta-text of Chivalry into the story in such a way as it would enhance the experience for people who "got" the visual meaning, while not dragging things down for people who didn't. So I cut this scene down to one panel.

The tapestry is a complete, long form comic strip created over 1100 years before some people claim comics were invented. So, I loved being able to reference it here.

But even more interesting to me are the sequential art sequences that appear in illuminated manuscripts - comics in book form.

I once got into a rather vicious argument with an academic who insisted illuminated manuscripts were comics. I said no. She said yes. Then she insulted the lowly comic artist and blocked me on Facebook.

Whatever.

My point was not that you can't find sequential art in illuminated manuscripts. My point is that an illustrated book isn't de facto a comic. Most illuminated manuscripts are illustrated books. Some illuminated manuscripts contain sequential art.

Just because opera is music, that doesn't mean all music is opera.

Just because comics books are books that doesn't mean all books are comic books.

And just because some illuminated manuscripts contain sequential art, that doesn't mean all illuminated manuscripts are sequential art.

But one is.

Let me show you it.

One of the earliest examples of an illuminated manuscript with comic art is The Bible d'Etienne Harding which you can see in this really bad jpg here, sorry, best I could find.

Created around the year 1109, property of a French Cistercian monk, it combines sequences like this with pages of text and illustration.

Not a comic book IMHO, but an illuminated manuscript with sequences of text, illustration and sequential narrative.

It's no more a "comic book" than a newspaper is for having text, illustration, and comic strips in it.

IMHO, academic lady.

And here's a look at the Old English Hexateuch (hexateuch refers to the first 6 books of the Bible) which I think is far more visually complex and interesting work, and comes much closer to the illuminated manuscript as comic, but still intersperses large sequences of text and illustration with sequential storytelling sequences. So I don't consider it a comic, but a book with sequential work in it.

Now this work below is a different matter. This is from the Holkham Bible Picture Book, circa about 1330.

This thing is genius. It measures a little larger than a modern comic, around 8"x11", and almost every page of it is like this spread here. 231 pages of beautifully rendered art, with repeated use of banderoles - "speech scrolls" (basically word balloons) - and captions, and (mostly) real sequential art. I've never seen anything else that comes even close to it, and by all accounts, neither has anyone else.

It may not be a modern comic book - but it's a comic book as far as I can tell. I don't think there's any other illuminated manuscript that is as complete, sophisticated, and innovative a sequential storytelling work.

If this were printed and seen by more people, the comic book medium would have taken off centuries earlier. But it wasn't. It was tucked away in a monastery somewhere and few people ever saw it. It ended up being forgotten for centuries until it popped up again around 1816 when a banker sold it to an avid book collector, Thomas Coke, Earl of Leicester, who inherited Holkham Hall and its library and set about restoring and expanding it.

The banker wrote, “a very curious MS. just brought here from the Continent. . . which I think one of the greatest curiosities I ever saw”.

Sequential art got invented over and over and over by one artist after another until one day centuries later, some teenaged boys found their newspaper strips gathered together in a cheap format, and suddenly comic books were popular and like new.

And then a lot of people who didn't seem to realize that books had had pictures in them for centuries got all up in arms about the harms of books with pictures in them.

I think it's funny that it is called the Holkham Bible Picture Book. There really was no "comic" art language when this work was created or when academics began to catalogue this sort of thing. Will they change the name now?

Who can say.

Anyway, another Holkham Bible Picture Book reference for you.

Look familiar?

I referenced it in this scene in Chivalry.

One of the fun things about the Holkham is that it opens with a discussion between a friar who has commissioned the work and the artist. The friar admonishes the artist to do a good job on the project because it will be shown to important people. And the artist responds, "Indeed, I certainly will and, if God lets me live, never will you see another such book."

He wasn't kidding.

You can see the entire manuscript HERE.

Thank you, Colleen. This is a very informative piece about the history of sequential art. I am impressed that you did a homage to the Bayeux Tapestry in “Chivalry”!

Just in case anyone else tries to follow the link to the illustrated manuscript; that bit of the British Library website is still down from the cyber attack they've been suffering for months.

I really wanted to see the banderoles!