Very Bad Publishers Part II

Sometimes you’re the pioneer and sometimes you’re the canary in the coal mine.

Very Bad Publishers Part I is HERE.

Being the first mover in a new market can be a real advantage. I’ve been on the first mover end of a lot of comics industry events: the black and white boom of the 1980’s, the self publishing boom, the independent press, yadda yadda.

While being a pioneer gives you the opportunity to scope out a new arena and experience explosive growth in a market without much competition, pioneering anything is high risk. You experience the explosive growth before you can build up a back end plan to minimize risk. And since you start off with little or no competition, you may not be prepared the day the competition shows up.

Being the first mover gets you the new territory, but there’s no guarantee you get to keep it.

For example, lots of early US manga pioneers are sitting around with their mouths hanging open because they helped open a whole new market they are no longer in a position to take advantage of, which is why second mover advantage may be even more important than first mover advantage: you get to learn from your predecessor’s mistakes.

Almost everyone I knew (including me) who self published, experienced a blissful period where we managed to move a kajillion copies of comics one day that we couldn’t give away the next year. When there were 7 self publishers, it was easy, but when there were 1000 of them, we had a problem.

Ancient History: Frank Miller, Don Simpson, Larry Marder, Jeff Smith, and me. 1994-ish, back when self publishing was cool. And easier to get attention for your book than it is now.

Here’s a good overview of:

Sometimes your first project, or some other early project is a hit. It sells very well, gets lots of good notices, and you sit around congratulating yourself on your creative genius, for surely there can be no other reason for your great success than your innate wonderfulness.

Well, sometimes the reason has absolutely nothing to do with the quality of your work. Sometimes, you are just the only horse on the race track.

In the early days of the independent comics press you could count the number of small press publishers on your fingers. Today, there are hundreds.

When I was a kid, I got a distributor catalogue for independent comics – the old Moondance catalogue. It was only a couple dozen pages total. Today, the Diamond catalogue is hundreds of pages long with thousands of products listed.

In the early days of graphic novels, there were no more than a few likely GN offerings in an entire year.

Now there are hundreds of terrific books to shuffle through on the front and backlist offering every single month.

A big graphic novel sale in 1981 was a very nice event, but it is not nearly as impressive as a big graphic novel sale today. In 1985, you might find no more than a half dozen GN titles in a major bookstore.

Now, hundreds of titles compete for rack space and a breakout hit goes to big name authors like Neil Gaiman who gets his Sandman GN noted on the New York Times bestseller list. Accomplishments like getting on the Waldenbooks trade paperback list are now…what, is Waldenbooks still in business?

In the end, sometimes your sales aren’t always about you. Sometimes timing can be everything. And first mover advantage is something that only happens once.

The market forces that allowed a book to sell well in 1981 don’t exist anymore. And the creators who made big numbers in 1981 were being left behind in 1991, angrier by the minute, wondering where their audience went.

By 2001, these creators were selling off tangible assets.

Market Paradigm

The market is constantly changing. If you are not paying attention or if you spend all of your time trying to adapt to the market as it is today, you are already being left behind. While you are trying to live in the present and make it work for you, others are looking at the future and creating an industry paradigm you won’t recognize and a market for which you will no longer be qualified for employment.

This industry is a pop culture industry, and if the popular in your pop culture isn’t progressive, you are obsolete before your book even comes out.

My old publisher was woefully out of touch with market forces and trends.

One little example:

At the same time Bill Sienkiewicz was painting the incredible Frank Miller Elektra graphic novel, my ex publisher was touting its new “painted” 64 page graphic novels as the hottest new trend in publishing.

“Did I say painted? You betcha, pilgrim!” enthused one press release in their sad attempt to imitate Stan Lee’s hyper-enthusiasm and cameraderie.

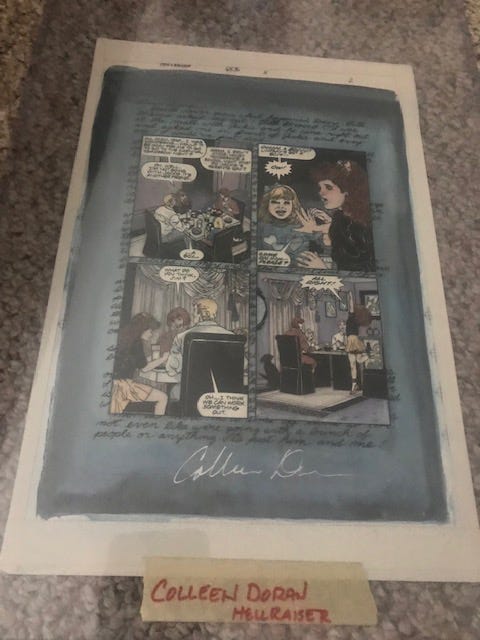

Yet these painted GN’s were created by xeroxing black and white art and using Doctor Martin’s dyes to color right over the drawings, a process Marvel Comics had been using for years. I colored some of my work on Clive Barker’s Hellraiser for Marvel’s Epic division using the same technique only in a more sophisticated fashion. The blue line color process allowed the artist to paint on a - to the camera - invisible blue lined copy of the art while a black plate kept the clean black lines separate on an acetate overlay. There was no qualitative difference in the painting processes except the Marvel process was cleaner in final reproduction.

All of the black line you see above is on an acetate overlay. All of the color is on a separate bottom sheet.

My old publisher was blissfully unaware that this process had been used for years, and so considered themselves pioneers of some sort while Bill Sienkiewicz was wowing the masses with hundreds of acrylic pages painted for Elektra. In no time at all, Dave McKean was blowing everyone away with his paintings on Black Orchid and Sandman while my old publisher was still trying to perfect coloring within the lines.

Before any of my old publisher’s GN’s were released, every single “innovation” was years out of date.

Even their market paradigm was years out of date.

Accustomed to having one book that did very well in bookstores, they neglected the burgeoning direct market almost entirely. While A Distant Soil had sold very healthy numbers in that market, the publisher made little effort to relist backlist copies of my book or anyone else’s books because that was not how they did business with their retail trade. Once solicited, no attempt was made to reoffer inventory even though no cost whatsoever was incurred in relisting books with Diamond or any other direct market distributor (at the time.)

No one at my publisher could be bothered to do so because the entire attention of the company was focused on the retail trade. The easy money in the direct market was ignored since the direct market was not a major force when this publisher began to do business. Therefore, they didn’t notice that the times had changed and did nothing to take advantage of the new market paradigm.

Backlist is the backbone of GN publishing. Most of the cost of the book is paid for in the initial release of the book, but the profits are usually in reorders. If a book has long term potential, the reorders can go on for years. These books are known as “evergreens”.

However, care has to be made when calculating the number of books to print. It’s often little more than a gamble when making a print run decision.

Say your initial orders come in at about 3,000 copies. Your printer will give you volume discounts if you order books in greater quantity. So, if you only print 1,000 copies, you may be charged $2 per book. But if you order 5,000 copies, you will be charged $1.75 per book.

However, if you only get orders for 3,000, how do you know you will sell 5,000 in the long run?

Without some kind of track record for the creator or project, on that first book you are gambling that the extra run of books that you will order to warehouse will eventually sell and that you will save money in the long run by ordering 5,000 books even when you only got orders for 3,000.

Remember, you’re only saving a quarter a book by upping the print run. Is that quarter a book worth the risk of losing a few thousand bucks because you have bought books you can’t sell?

You may sell them all, or you may end up with 2,000 books in which you invested $1.75 each, which adds up to a big, expensive stack of worthless paper.

You need to determine the economic order quantity by calculating the per copy cost of printing versus storage, taxes, spoilage, etc. Will that investment of inventory save you money or could that money that was spent on creating inventory be better used to pay off bills or to invest in other projects? It can be an educated guess or it can be a gamble.

And my ex publisher liked to gamble.

They gambled big. Bigger than big.

Far from content to print 5,000 books when they got orders for 3,000, it was not unknown for them to publish 10,000-12,000 books when they got orders for 3,000.

On one book, they gambled so big I simply could not believe it.

When The Woman was unhappy with the printing on the first print run of the GN I had illustrated for her, she ordered the entire print run be redone from scratch. The first print run was 12,000 copies against an initial order of 3,000 copies…ludicrous.

I hated the reproduction, too. The publisher had botched the color separations badly and everything on the light side washed out while everything magenta went screaming red. This was, in part, due to using Dr. Martin’s Flourescent Watercolors for the painting.

There’s a long, grim explanation of what can happen when your printer doesn’t pay careful attention to settings, especially when shooting flourescents (everything is done digitally now, but whatever, back then this was done by camera) and what your eye sees is not what the camera sees. A computer scanner can’t “see” flourescents properly either.

But whatever...

Since the publisher was owned by its printer, quality control was problematic. The printer was the boss, not the publisher, and the printer liked to cut corners. But I would never have dreamed of trashing the print run and taking that kind of financial risk. I would have sucked up the mistake and moved on. In fact, I had once printed an issue of A Distant Soil with a page out of order…issue #9. (A third party informs me that another graphic novel was released with six blank pages. Boy, howdy.)

As editor in chief, The Woman claimed to me she had ordered the initial print run on her book destroyed, which would have made it a non-existent book. But she was unable to resist the idea of stamping the second try at the color separations with a Second Printing. That made it look as if the first printing had sold out instead of having been pulped, which made the book seem more popular than it was. They printed another 12,000 copies.

The first print run was never destroyed, however.

So, for a book that had only 3,000 orders, 24,000 copies were printed in only a couple of months resulting in a $24,000 minimum investment for the publisher in printing alone on a book that could not possibly have earned more than $9,000 gross.

Some months after all of this, when it not only became apparent that I was simply not going to be able to work with The Woman (especially on a book that had only 3,000 orders,) I asked the publisher to release me from the contract. He agreed. He was hemorrhaging money on it. In the six months since publication, there had been virtually no reorder activity. Future volumes looked to be losers, too.

You can always go back to press with a book. If it sells really well, reprint it. But overprinting has sunk many a small press (so many stories about Comico to insert here, I can’t even). If those books don’t sell, you can’t pay the rent, you can’t pay your printer, and you sure as heck can’t eat the books.

Frank Miller, Larry Marder, me and Jeff Smith sometime around 2010. Surviving. Don Simpson is still making comics, too, but he’s just not in this picture…anyway…

Okay, here’s what we learned about what I learned:

First Mover Advantage is fine as long as you have it, but it doesn’t last and that first flush of success is not always about you.

Second, pay attention to the industry around you. You can get so caught up in trying to be good at what you are doing right now, you may not notice that no one cares about what you are doing any more. The readers have already moved on to something new.

Computer coloring has put many a comic colorist out of work. Those that invested in new equipment and learned to adapt are working today. Those that didn’t don’t work at all. Adapt or die.

Third, Economic Order Quantity is the backbone of GN publishing and since most of the comics industry is periodical oriented, this has been a hard lesson for some folks. It’s sent many a small press down.

I haven’t been hit as badly as some folks because I learned my lesson from this old publisher. When I was self publishing, I kept my print runs close, as a rule. But there were a few issues where I got burned, particularly when I had guest authors I thought would sell well. Few did and I ended up losing money on inventory.

You also lose money warehousing that inventory. Storing books costs money when they don’t all fit in your garage! If you are paying for warehouse space, whatever the heck you saved on the overprinting for backlist is eaten up in rent in short order.

The rule of thumb: don’t print more books than you can sell in a year. I often print more than that of A Distant Soil because my overhead is so low. If my overhead were higher, I would print less.

When self publishing, I did well by warehousing my comics too, and I often relisted my comics to good effect. Sometimes I sold as many as 1,000 back issues a month. Not bad! But when the market collapsed in 1995, I got hit just like everyone else and had many comics I could no longer sell.

Fortunately, I hit on the idea of using the unsold backlist as promotional items, and now have almost no back issues left - some of them are worth a lot of money all these years later, and I hate myself for that.

But I know one self publisher who ended up having to scrap over 100,000 unsold comics when the market hit bottom in 1995.

Ow.

So, that’s what I learned for this go ’round…Stay tuned for Part III.

Originally written in 2003. Edited in 2023.

Colleen, I have always thought of you as a pioneer who has steadily forged forward through many different eddies and flows, tides and typhoons. I had no idea that you did so while bailing out crafts that shred behind you. I know you learned from these lessons but I wish it had been smoother sailing. At least the pens have never been knocked from your hands.

Too bad the Woman didn't do a press check. Where you go to the printer and okay the color while the press being made ready.